April is truly spring in Big Sky Country. Rain is suddenly more common than snow. The Mountains are still white with the winters snow, and are still gathering snow, some of the best of the year, and that will sustain us throughout the summer. The trees have these weird things on them. Oh, those are buds! The trees are actually alive after all. Insects are emerging throughout the afternoon, especially on overcast days. Most importantly, the trout are on the feed.

The trout don’t mind a little snow. Here we found a nice pod of brown trout rising to pupating midges stuck below the surface film.

In April we see nearly every river in the state exhibit some of the best fishing that we see all year, and very few are out and about to enjoy it. “Pinch me I must be dreaming” I incessantly repeat.

What makes April so great? Hatches, water temperature, minimal angling pressure the last 6 months, and the annual rainbow trout spawn that sustains all our addictions.

Let’s delve into the April hatches we see in southwest Montana.

Trout, especially ones smaller than 18 inches are highly reliant on insects to sustain their current condition and grow into the trout we really want to catch. April sees a number of notable insect emergences across the rivers we frequent in southwest Montana. From big stoneflies like the Skwala, to minute midges, we see are range of bugs throughout late-March and into April.

The Skwala Stonefly (genus – Skawla) has three species (compacta, americana, and curvata) that are only distinguishable by examining the genitalia under magnification. That seems a little extreme to me and sexually perverse to others. The magic of the Skwala is its size. These robust insects range in the 10 to 12 range and provide dry fly fishing that everyone can see. They exhibit similar hatching behavior to their larger brethren the salmon fly and golden stoneflies where they migrate from the larger cobble in the middle on the river to the banks where they crawl on the banks and emerge leaving behind a skeletal shuck that’s the tell-all indicator that these insects are present. Where the differ is we don’t observe the big “flights” before they obi-deposit. So if we find a few shucks, the weather is calm, and the sun is bright we will try our hand at fishing the big bug. We see skwalas, at our elevation, in late March or early April.

Only Louis Gaudet can truly capture the magic of spring insect life. Here we see a Skwala stonefly making fast friends with a Brachycentrus caddisfly

The Blue Winged Olive, Baetis, BWO, blue quills, olive quills are one of the most important western insects, and seemingly impossible to accurately identify and stay current on their current taxonomy classification. Because of that I won’t even venture into what they really are, because frankly I don’t know anymore. This diverse and expansive group of insects have dun colored wings and olive-colored bodies. They are multibrooded meaning that we see multiple generation of the insect throughout the year. We see the biggest insects in the spring and the second generation (fall are 1 to 2 sizes smaller). In the spring we see excellent hatches of these olive quills on overcast days with low pressure. Rainy days are a bonus as we see the hatch “pulse” as the rain comes and go. The primitive nature of mayflies means that they cannot produce moisture and are susceptible to drying out on warm sunny days. On cool days these insects float to the surface shrug their shuck off and then must dry their wings. The nastier the weather the longer the dry time leaving these delicious “sailboats” on the water longer providing outstanding dry fly fishing. The emergence of the baetid family is clumsy at best. They float to the surface via accumulated nitrogenous gas creating high concentrations of insects just below the surface, right under the surface, and on the surface of the water. This means we get to employ a number of patterns from floating nymphs, cripples, emerges, and duns. The females of this family exhibit neat egg laying behavior in that they crawl into the water to deposit eggs creating some exciting tight line swinging whenever the bugs are present. We see insect activity any time the water temperatures exceed 40 degree which is typically observed in early March and throughout April.

Rainbow trout seem to especially key in on baetis nymphs as they tumble across shelves during the emergence process.

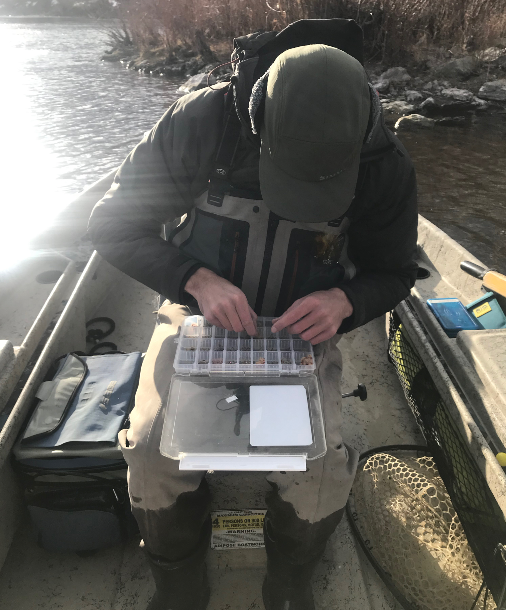

Midges, Chironomidae (family) have a couple thousand species in North America alone and range in size from 12 to 28. Again, another insect that is truly impossible to identify stream side, but easy to match in size, color and fishing technique. We see midges in cream, black, red, brown, and olive commonly. Midges that are red in color are most common in sediment rich areas. What gives the red color is hemoglobin as it binds to oxygen and that causes a conformational change in the molecule that causes red light to be reflected. How does that relate to sediment? The sediment rich environments create an anaerobic zone (without oxygen), so they hold onto their own. Midges buoy to the surface with accumulated nitrogenous gas and concentrate below the surface. They then emerge and mate above the water. Here they skitter about and cluster up. We see midge hatches throughout the year but early in the spring when they are the only active insects, we can find some pretty exciting and technical dry fly fishing. You would be hard pressed to find a more effective fly than a midge larva in the spring.

March browns (genus Rhithrogena) have multiple species, but all are robust clingers and thrive in the moderately paced riffles that characterize our freestone fisheries. They are like little suction cups and use well defined legs and gills to hold onto the rocks in which they live. As the water temps exceed 42 degrees these mayflies shed their shucks on the bottom of the river and head for the surface. Because of this unique behavior we see great wet fly fishing during their emergence. What makes this hatch so exciting, other than its timing, mid-March on area freestone, mid-late April on the Missouri River is their size. Nymphs can be up to a size 12 and the adults are usually a size 14. On our smaller freestones, it doesn’t take but a few of these insects to get the fish looking toward the surface and we find success fishing a light dry dropper set up on warmer days throughout March.

Mother’s Day Caddis (Brachycentrus occidentalis) are the last stand for our spring dry fly fishing. Following this epic hatch, sometime during this epic hatch runoff strikes and we see the rivers swell and the water brown. We see especially heavy hatches on the Yellowstone and Madison Rivers, but we also see them on our smaller freestones. The nymphs become incredibly important in the weeks preceding the hatch as they dangle from their silk tethers and feed in the broad riffles. Here they are picked off by trout. As water temps reach 50 degrees, we see insects begin to emerge. At 54 degrees we see hatches that are stifling, to put it lightly, and nearly every fish in the river feeds to the point of overindulgence. These caddis flies are robust and a true size 16. Oftentimes when the hatch is on, we fish larger attractor patterns as imitative flies are lost in the globs of adults and egg-layers floating down stream.

I wonder what they’re going to eat tonight? Mothers day caddis clinging to the windshield of Louis Gaudet’s faithful Nissan.

In short, plenty goes on in April. If we don’t see a hatch, chances are we will experience some of the most productive subsurface fishing of the season with so many insects present in the drift.